Jonis Agee

Around me the house, the people, the animals make decisions. The toaster produces the amount of browness it considers right; I can’t get it browner, burned almost as I like it, no matter how many times I punch it back it returns just as quickly. It makes these decisions, I am not certain that they are made in my interest, I suspect I have little to do with it, no reason to think so, I don’t want to anthropomorphize or anything, that could be foolish, assuming that the toaster oven in the corner under the cabinet to the right of the sink cared about me.

I go upstairs and prepare to type, turn on the heater in my little room, hoping that the dust that has settled into its coils all summer does not come whooshing out and activate my allergy, not intentionally, you understand, I don’t think that the heater holds a kind of malevolence in its metal brown grid. Then I scoot into my adjacent bedroom for some thick socks since this add-on part of the house is always cold and the floor, though it has another beneath it, is icy on my feet. My neck is sore, I can barely hold it up I notice, from the Indian leg wrestling I did last night with someone a hundred pounds heavier and eight inches taller. I thought I could win, in fact I could not believe that I could not win. Now it’s more doctor bills and silly explanations, but I had a choice, I understand that—break my neck or not, and what’s interesting is that I keep repeating the defeat, biting hard on my tongue each time.

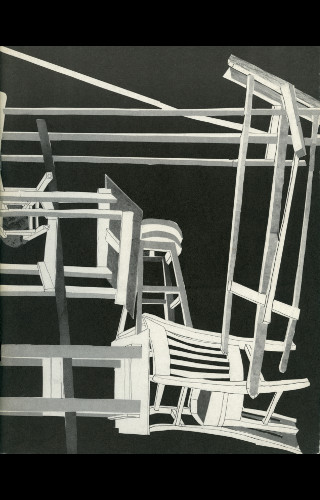

When I come back to the little room prepared now for the work ahead, I see that my stool is not in its customary place in front of the typewriter. That means that it is serving alternative duty as a TV holder in my daughter’s room. I turn around twice on my way in there, I would like to say that I thought about it like that, that something said to wait, maybe I could sit on something else to type, maybe I could wait to type, but then I just wanted the stool, she would be asleep after all. As I open the door, I don’t even glance at the bed so certain am I that she is asleep, and like the way I used to enter my older sister’s room, the one who slept all the time in a nest of her anger and dislike for me, I always tried to pretend that I wasn’t there, that I wasn’t going to her closet to get something, I mean I always thought that maybe I could get away with it like that, that somehow she wouldn’t notice as I pulled the little closet light on so it shone on her bed and her face, because what I wanted to avoid was that voice that came through me like a knife, that pierced all my intentions, good and bad, with the clarity of its utter disdain.

So I didn’t glance at the bed at first but the scurry, the sudden movements, not even a cry, a sound but louder than that, made me look and there they were, my daughter’s face like an animal’s, hollow with surprise and fear.

Again I turn around to leave but realize that now more than ever I need the stool, and foolishly I turn again, ignoring the stereo rock softly orchestrating the room’s behavior, the flickering candle, but it’s morning, I want to say and reach out for it, tidy up, I have this sudden urge to tidy up the room, to go downstairs for a giant green plastic garbage bag, to throw all the things around me into it, the bottle and the cigarette butts, the plates of dried food, the records and the stereo, the candle, of its old and useless enough, and I could make the bed up and put them back to sleep, put them back into it, cleanly without the mess, but I don’t touch anything, I lift the TV, too heavy I know, but don’t think about it this time, and then suddenly there is nowhere to put it, as I try to set it gently on the floor I am aware that a rather large brown tennis shoe is obstructing its balance, I push at it, halfheartedly with my foot, but can’t budge it really on the thick carpet, the rubber sole is too adhesive and I give up, placing the TV at some drunken angle on the spine of the shoe, only now as an afterthought, that it might ruin the shoe’s conformation, and after all they weren’t that old. Then I glance over again to the bed, only then, and only to the bottom next to me, I am close enough to lean over and touch it, and the covers have pulled up and away now, a tangle of feet there, remarkable feet I think, those thin boyish legs kids that age share in common, and his larger feet some promise of later and her’s smaller and what they will be forever, and around his ankles, in a hurry, his underwear, and this somehow saddens me, and no, I am not angry.

Get dressed I say, and we’ll talk…But I don’t mean it, as I pick up the stool and stumble apologetically from the room, remembering to close the door just as she likes, quietly and firmly.

Jonis Agee is the author of twelve books, including five collections of short fiction (Pretend We’ve Never Met, Bend This Heart, A .38 Special and A Broken Heart, Taking the Wall, Acts of Love on Indigo Road), six novels (Sweet Eyes, Strange Angels, South of Resurrection, The Weight of Dreams, The River Wife, The Bones of Paradise), and a book of poetry (Houses). Three of her books, Bend This Heart, Sweet Eyes, Strange Angels, were named New York Times Notable Books. She has been awarded fellowships for writing from the National Endowment for the Arts in Literature, the Loft-McKnight, the Minnesota Arts Board, the Nebraska Humanities Council. She has been given The John Gardner Fiction Award, the Mark Twain Award for Contributions to Midwestern Fiction, the AWP George Garrett Award for Service to Literature, two Nebraska Book Awards, and Forward Magazine’s Editor’s Choice Award for Best Book of Fiction and the Gold Medal for Fiction. She currently teaches at the University of Nebraska-Lincoln. She lives in Omaha on the bluffs above the Missouri River with her husband, Brent Spencer, where they have recently founded a literary press, Brighthorse Books, publishing fiction and poetry books. Her new novel, The Bones of Paradise, will be published in August 2016 by William Morrow.