Lyricism is a trademark of Stuart Dybek’s writing. The music of his prose and the dreamlike shifts throughout his narratives have his readers frequently describing his stories as poetic. He is the author of two short story collections, Childhood and Other Neighborhoods (1980) and The Coast of Chicago (1990), as well as a novel-in-stories, I Sailed with Magellan (2003). These stories have been acknowledged with several awards, including four O. Henry Prizes and several appearances in The Best American Short Stories series. In 1995, he received the PEN/Malamud award for excellence in the art of the short story.

In addition to the literary awards, Dybek’s writing has won him a devoted audience of readers, many of whom are writers—both of fiction and poetry. As such, it’s of little surprise that Dybek’s first published book was a collection of poems, Brass Knuckles, which appeared in 1979. Twenty-five years later, Dybek’s second collection of poems has arrived. Streets in Their Own Ink (Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2004) offers a somber tour where stark realism, dark humor, and religious visions are encountered throughout the late-night urban terrain. Poems from his collection originally appeared in publications such as Poetry, TriQuarterly, and The Iowa Review, and also made an appearance in The Best American Poetry (2003). Also, in 2004, Carnegie Mellon University Press brought Brass Knuckles back into print.

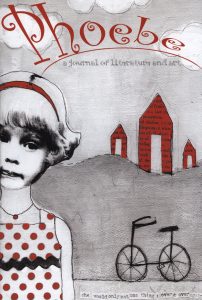

Publishing in more than one genre makes for great demands on a writer’s schedule. Phoebe is grateful that Dybek was willing to make time to discuss his thoughts on writing fiction and poetry.

Ryan Effgen: What were some of the first things that you wrote?

Stuart Dybek: I suppose I first began writing as an undergraduate or maybe even as a senior in high school. Suddenly I began to associate writing with music. I was trying to play the saxophone, and I was in a few bands. At the same time, whatever impulse was asserting itself in my life through music was also being expressed through writing. I think my model for that was, in part, the beatniks. They had already been around, but I was just getting acquainted with them. They had a huge interest in jazz, as did, say, Lenny Bruce and a lot of stand-up comics I liked. And so my mind kind of forged a connection between music and comedy and poetry and fiction. I began to think of them as aspects of a similar mindset. So I always wrote fiction and poetry simultaneously.

It’s been twenty-five years since Brass Knuckles (1979) was published. Where were you in your life when you wrote the poems in that collection?

The poems in Brass Knuckles go all the way back. Not that an apprenticeship ever ends, but there’s certainly a period of life when you’re very aware that you’re in an apprenticeship—and I mean that’s how far back a lot of the poems in that book go. Some were written before I ever got to the University of Iowa. A lot were written while I was at Iowa, where I did classes in both fiction and poetry workshops, which was kind of unique for that program. I wouldn’t call it a wall between the two genres, but there weren’t really a lot of crossovers at that time.

Did you apply to the MFA program at Iowa as a fiction writer or a poet?

I applied in both. They wrote back and said, ‘Why don’t you pick one or the other? We’d prefer fiction.’ But when I got there I reapplied for poetry and then it was just a formality. I began to take workshops led by Marvin Bell and Donald Justice. It just kind of seemed like a natural thing to do.

Is Streets in Their Own Ink recent work or is it made up of poems spanning the last twenty-five years?

They’re really poems that I continued to write after the first book of poems was published. They span a really long period of time. Something that’s deceptive about books: you think the writer wrote the entire book shortly before it was published. Really, some of the poems in Street in Their Own Ink are much older than others. A selection process kind of set in. That is, I published way more poems than appear in that book, and I selected out the poems that I still liked enough to put in a book—plus poems that I felt went together. So sitting on the floor of my studio right now I have two other books nearly complete that I was writing during that same long period of time.

For you, is there a strong distinction between the two genres? Or is the distinction all that important?

You know, I think those kind of compare/contrast ways of thinking about subjects are extremely valuable, and that to counterpoint fiction against poetry—or prose against poetry—can lead you to interesting notions about both. But, for me, rather than seeing them in opposition, I see the similarities. It’s just a matter of what perspective you want to look at them from. And it’s led me to notions about writing that I would call overarching genre. So, I’ll give you two brief examples of what I’m talking about. For lack of a better word, let me call them modes. We identify poetry in the 20th and 21st century almost wholly with the lyrical mode. The lyrical mode is the mode in which we dream. In the lyrical mode you think through the association of images, and association is also what rhyme is about. Of course, poetry going all the way back to Homer is written in all kinds of different modes: the epic mode, the narrative mode, and so forth.

And we identify fiction with the narrative mode. The huge power of the narrative mode is that it makes us believe that, by stringing events along this narrative line, we can see the cause and effect. No matter how crazy the life we’re writing about, the narrative mode implies that life is rational. That because we can see this pattern: even though we might be writing about insanity, the pattern still insists that there’s rationality at the heart of life. And yet, some other fiction writers who have become the most prominent models in writing programs—Joyce, Welty, Kafka—are writers who work equally well in the lyrical mode. A story or poem is frequently not written in either the purely lyrical or purely narrative mode. In fact, it’s often the way that the writer combines those modes that makes the story or poem complex or interesting.

So, if you take a genre perspective, it kind of leads you to an unexamined reflex that poetry is all about lyricism and fiction is all about narration. The fact of the matter is, those modes assert themselves. They’re present in all the different genres including drama and the essay. And so that’s the way that I more naturally look at it. I see these overarching modes and that’s what interests me more as a writer than what genre they fit into. It isn’t that different genres don’t offer different possibilities. For one thing, each one comes with its own historical dimension, which is important. But also, in the 20th and 21st century, ever since modernism, there’s an enormous overlap between genres—whether it’s fiction and nonfiction, fiction and poetry, or what have you. That’s actually part of modernism—a lot of writers chose to position themselves in that overlap. The genres are easy to define at the extremes, but once you get into those gray areas, those overlap areas—such as the one between fiction and nonfiction, or between the short short and the prose poem—it’s the very blurring of lines that becomes interesting.

You’ve published three works of fiction: two short story collections and a novel-in-stories. Is there a kinship between short stories and poetry, not merely in the brevity, but in what they’d hope to accomplish—say, as opposed to the novel—that draws you to both?

I would make room in answering the question to say that there are novelists who are very interested in the lyrical mode—obviously Joyce was one of them—and if a prose writer is working in the lyrical mode, their work is going to have a relationship to poetry. You’re constantly hearing somebody say, ‘Joyce is a poetic writer,’ or ‘Scott Fitzgerald, in Gatsby, wrote a poetic book.’ What they’re really talking about is that those writers were comfortable in the lyrical mode. However, I think I do essentially agree with the implication of your question, which is that by its nature, the short story does have a lot to do with the poem—probably because it requires compression.

Does material that originally came to you as poetry get worked into your stories?

I’ve always written them both and just as importantly I read them both—I probably read more poetry that I read anything else. So when it comes to an early draft, especially where I’m kind of working with unshaped clay, I don’t mind borrowing. Frequently, something that starts out in one genre ends up in another. I’ve never had a story become a poem, but I’ve frequently had poems become stories. “Pet Milk” is one such story; “We Didn’t” is another. And so there’s a kind of failed or abandoned poem in the DNA of those stories in a way that there isn’t in say a story like “The Long Thoughts” [in Childhood and Other Neighborhoods], where almost from the start I knew that it was a story because it was just a retelling of an experience that happened in my life. There’s a quote from Ray Carver in which he says, ‘I couldn’t write stories if I didn’t write poems.’ Ray was a friend, and I think I know what he means. I never sat down and discussed that exact quote with him, but I think in part what it means is that a lot of what goes on in his stories was first generated in his notebooks as poems. And that’s true with me, the kind of sketches I make in notebooks are frequently sketched in verse. Because I’m used to looting those notebooks for stories I don’t have any reservations for looting poems either for that matter. And in a couple of instances, I’ve also looted stories for lines in poems.

As far as poems and stories feeding into one another, “We Didn’t” opens an excerpt from Yehuda Amichai’s poem “We Did It.”

We did it in front of the mirror

And in the light. We did it in darkness,

In water, and in the high grass.

– Yehuda Amichai, “We Did It”

We didn’t in the light; we didn’t in darkness. We didn’t in the fresh-cut summer grass or in the mounds of autumn leaves or on the snow where moonlight threw down our shadows.

– Stuart Dybek, “We Didn’t”

This serves as something more than an epigraph—the opening and closing lines of your story echo the poem. Did this piece start out as a reaction or response to Amichai’s poem?

I don’t use allusion all that much as a device, but that story certainly consciously used allusion and hopes that the reader picks it up. I didn’t expect the reader to be familiar with Amichai’s poem. I don’t really use epigraphs in stories all that often—it seems like a lot of baggage for a poor story to have to drag around—but in that instance I felt that the epigraph was an organic part of the story. And as long as I was making allusions to Amichai’s poem, I decided I would make some obvious ones to the Molly Bloom soliloquy: a bunch of Yes-saying goes on during one of the scenes on the beach. And something that I wouldn’t expect any reader to get—when the narrator describes his unfulfilled adolescent horniness—I went back to very early poems by Neruda, some of his earliest poems that he wrote while he was somewhere in Central America. Twenty Love Poems, they’re called. I borrowed a few lines from those as well. To my mind it was all being done in a playful way. And what generated that impulse was the fact that before that was ever a story it was supposed to be a poem that was a semi-comic reaction to the Amichai poem.

In addition to Amichai and Neruda, who are some other poets that are important to you?

Along with almost every other poet on the planet, I’d say Rilke. I also love Yeats. And a poet who’s really become a little unfashionable but I still think is a brilliant writer is T.S. Eliot—although his personality, as we’ve come to know since his death, seems a little off-setting. There’s a questions about anti-Semitism in his life that I don’t really see on the page, in the way one sees it in Pound. And above all those others, Eugenio Montale, the great Italian poet. And of course I can’t read him in Italian. Jonathan Galassi’s spectacular work on Montale has become available, so readers such as myself—who really don’t have a grasp on Italian, no matter how often they try—are really lucky that people like Galassi have spent so much time bringing this poet into our language.

One thing that’s always associated with your writing is a strong sense of place. There are very specific and geographically accurate details, real streets, real buildings, real places in Chicago. Unlike stories, poems aren’t always required to have a setting, although the poems in Streets in Their Own Ink contain a few specific references to Chicago. Do you feel that these poems are coming from the same setting as the stories?

I was a little surprised, when the books came out, that the Chicago stuff had come to so dominate discussion of them. But on the other hand, it seems ingenuous for me to make disclaimers about that, since I studded the stuff with so much Chicago material. But I thought in the book of poems that Chicago was more an image for all urban experience. The way that I’ve always felt about setting is that what it captures externally is important to orient the reader, and for its sensual qualities, but that setting is almost invariably also an image of a psychological state. So that in a book that’s so nocturnal in character and the streets are labyrinthine and you get this constant walking, the external setting hopefully mirrors some kind of a psychological state. I felt that to be more true of the previous book, The Coast of Chicago, which is also very nocturnal, and has these nighthawk things in it. I really felt that there was more cross-talk between that book and Streets in Their Own Ink than with Magellan.

A number of your stories are non-linear; “Paper Lantern” and “Pet Milk” come to mind. Do you think that working in poetry—where you’re not strictly obligated to have one thing causing the next—has fed into writing stories that avoid the linearity of narrative?

I think it has, although one doesn’t need to turn to poetry for non-linear models for fiction, certainly. That’s the whole point of the lyrical mode: one thinks through association. Time becomes different; lyrical time is much different from narrative time. Instead of creating the illusion of narrative time, you can slow time down, you can speed time up, you can try to abolish time. So it avails the writer of this other way that human beings think. But my feeling really is that a writer might have individual leanings and strengths and so forth, but that the best thing is to acquaint yourself with all the various possibilities and kind of reflexively adapt into whatever particular project you’re working on.

Ryan Effgen’s short stories have appeared in Best New American Voices, Fiction, Pindeldyboz, and Painted Bride Quarterly. One reviewer of Best New American Voices wrote, “The best of the ‘Best New American Voices 2007’ may well be Ryan Effgen.” His story from that anthology has been adapted into a short film which premiered at the 2009 Charlotte Film Festival. He was one of five authors to be awarded a Virginia Commission for the Arts Fiction Fellowship. While earning his MFA, Ryan served as Editor-in-Chief of phoebe and worked for two years at the PEN/Faulkner Foundation. His website is http://www.ryaneffgen.com/.

Stuart Dybek

From Northwestern University where he is a Distinguished Writer in Residence:Stuart Dybek is the author of three books of fiction: I Sailed With Magellan, The Coast of Chicago, and Childhood and Other Neighborhoods. Both I Sailed With Magellan and The Coast of Chicago were New York Times Notable Books, and The Coast of Chicago was a One Book One Chicago selection. Dybek has also published two collections of poetry: Streets in Their Own Ink and Brass Knuckles. His fiction, poetry, and nonfiction have appeared in The New Yorker, Harper’s, The Atlantic, Poetry, Tin House, and many other magazines, and have been widely anthologized, including work in both Best American Fiction and Best American Poetry. Among Dybek’s numerous awards are a PEN/Malamud Prize “for distinguished achievement in the short story,” a Lannan Award, a Whiting Writers Award, an Award from the Academy of Arts and Letters, several O.Henry Prizes, and fellowships from the NEA and the Guggenheim Foundation. In 2007 Dybek was awarded the a John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation Fellowship.