K.E. Semmel

I have a word of the day calendar of forgotten English. Each day, I can tear off a page to get an odd and generally useless word that has long since disappeared from everyday speech. The day I interviewed Joyce Carol Oates, August 12th, I was struck by the day’s word: oneirocritick. According to Stephen Jones’s 1818 book Pronouncing and Explanatory Dictionary, my calendar informed me, the word means: “An interpreter of dreams.” How appropriate it seemed. How fortuitous. Joyce Carol Oates is an interpreter of dreams.

Joyce Carol Oates has written more than eighty books. Besides her impressive long novels, including the National Book Award-winner them (1969), Bellefleur (1980), You Must Remember This (1987) and Blonde (2000), Oates has produced critically acclaimed volumes of poetry, plays, short stories, novellas and essays. Her short stories, widely anthologized, are regularly included in Prize Stories: The O Henry Awards, The Best American Mystery Stories, the Pushcart Prize Stories, and the Best American Short Stories.

Critics and admirers alike often note the astonishing rate at which Oates publishes her work. The rate of publication is impressive, of course, but what’s even more impressive is the vocal range she displays. She can easily enter into the lives of serial killers, murderers, high school dropouts, college professors, lawyers, and doctors. From her first collection of stories, By the North Gate (1963) to her most recent book, The Falls (2004), Joyce Carol Oates has continually pushed fiction in new directions, shaping it and reshaping it according to a need to find the best way to tell the story.

She is an interpreter of dreams, all right, and her dreams are rich and rewarding reads.

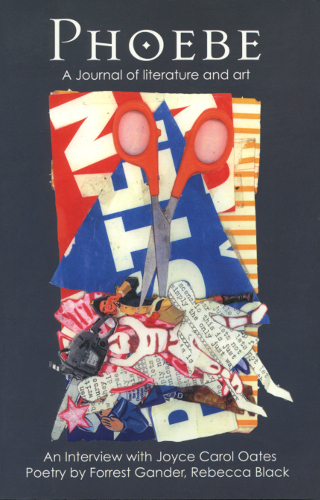

This year, Joyce Carol Oates was the recipient of the third Fairfax Prize for Lifetime Achievement in the Literary Arts at the Fall for the Book Festival at George Mason University. We at Phoebe are pleased to bring you the following interview.

* * *

Phoebe: You have written numerous stories and books set in a fictionalized location in western New York State, Eden County. How do you determine when to use fictional place names—Eden County, Port Oriskany, Mt.Ephraim—with real places, Buffalo, Olcott, Ransomville?

JCO: I kind of bring together the two. One is mythic and somewhat historic and then the other is real and authentic and on the map to suggest that the two regions are simultaneous. It’s somewhat deliberate. In the very beginning I had all fictional cities, except maybe for a large city like Buffalo, because you can’t in a sense invent a really large city in America. You know there is Buffalo and there is Syracuse and Rochester. You can’t somehow invent cities of that size and make it seem plausible. So it’s a mixture.

Phoebe: You once wrote in a journal entry,”[I]n most good writing the setting is one of the characters, one of the most important characters. It speaks. It lives.” Can you tell us what you look for in a setting that can give it that quality of aliveness you’re seeking?

JCO: There’s a certain visual vividness that I look for in my own writing, and other people’s writing too. I read to be transported to a world I’m not in at the moment. So the visual is very important: selected details that bring you right into a world. And different sensory impressions like smells or the feel of the atmosphere; and then of course the way people speak. And the way they interact with their environment. I tend to be more oriented toward the rural in America than toward the city. I have written stories and novels set in cities, but I just feel a little more comfortable toward the rural.

Phoebe: In the afterword of Where Are You Going, Where Have You Been: Selected Early Stories, you write that many of the stories in that volume are in a mode of narration you call “literary-oral.” Do you continue to see your stories as being in the literary-oral mode?

JCO: Yes, I think most of my stories—and certainly the ones that I read aloud to audiences—are of course literary, but at the same time it’s as if somebody is thinking or even talking; a person who is not the author but a character. And so I try to calibrate the language, vocabulary, the sentence structures to make them seem plausible for the person who is being narrated.

Phoebe: The original publication of “Where Are You Going, Where Have You Been” was famously dedicated to Bob Dylan. I’m struck, forty years later, by the similarities in your careers as artists. Do you feel a particular kinship to Dylan today?

JCO: Well, Bob Dylan is a very important American artist and he’s almost my contemporary. His music was so important in the 1960s in a certain part of America—I mean a certain age group; just very, very important. And he stayed with us over the decade changing his music and changing his attitude, I guess. For a while he was a born again Christian. I guess he’s moved away from that, I’m not sure. I don’t follow Dylan’s musical career now. But yet I still feel he’s very important and that I might someday soon feel a rekindling of interest in him.

Phoebe: Over the years, many commentators have criticized your stories for being too “violent,” or for not having “feminist” themes. What seems more important is your incredible ability to enter into and out of any character, male or female, black or white, and make that character seem astonishingly real. At this stage of your career, do you feel critics have finally freed you from the cages in which they wish to place you?

JCO: Well that’s an interesting question. I don’t read too much criticism of my work. If my editor sends me something and says you must read this, then I will read it. But I don’t really read too much of it anymore, which I think is typical of most writers. There are some artists and filmmakers who never read their reviews, because a bad review would be very injurious, and hurtful, and discouraging. So, when you’re an artist you have to be encouraged almost everyday of your life. You have to feel what you’re doing is appreciated in some corridors. So I tend to avoid reading too much about myself for fear that my energy will be depleted. But I have certainly learned from many reviews, and there have been a lot of good critical essays on my work, and very intelligent responses, like Greg Johnson’s biography. So definitely I do read some criticism with much appreciation.

Phoebe: You have written a number of very distinctive novels throughout your career—most recently Zombie, Black Water, Foxfire: Confessions of a Girl Gang. When you write stories that depart from more traditional voices, how do you separate your creative brain from your inner-editor that tells you, “You can’t do this; readers won’t like it”? Or can you simply freeze this voice out completely?

JCO: Well I guess I don’t try to anticipate readers. I feel that one really can’t do that. It’s more that I think in terms of separate scenes and chapters in a dramatic way. Sometimes I sketch out a chapter as if it were a little play. I have a very cinematic and theatrical imagination. And then I tell the story again, but it’s overlaid with a narrative voice. I try to be faithful to the vocabulary and the intellectual level of the people about whom I’m writing. So in a novel like Foxfire: Confessions of a Girl Gang all the girls are teenagers, or young teenagers. So I have to calibrate that vocabulary so it doesn’t seem too mature. But at the same time it’s not just the realistic vocabulary as if I were making a tape recording of some high school kids. It’s a mixture of the two.

Phoebe: Do you see your short stories as a kind of laboratory for exploring material, themes, and modes of narration that would be difficult to pursue in a novelistic form? Or that you would like to pursue in a longer work, and are only testing out in the short form?

JCO: Well again that’s a good question. The novel generally comes as a concept that involves many characters and a period of time that’s ambitious. And a short story usually comes to my imagination as a story that involves maybe one, two, or three people at the most, and probably a very short period of time. I would love to write short stories—I’ve only done of few of them—that take place within an hour, let’s say that’s a kind of Edgar Allan Poe idea. There’s something about that finite form. Aristotle speaks about the Unities, and that really is very dramatic and tight. But with a novel of course you can’t do that; so the two are really kind of different in my mind. Sometimes I see a short story getting longer and longer and it should be maybe a novella. It would probably not be a novel.

Phoebe: Did you see that with Zombie?

JCO: Zombie was a short story first. Yes, that’s a very good example. Zombie was a short story; it was published in the New Yorker. And I got so many responses to it and I looked at it again and I thought: Really, it’s not complete—it’s like part one, I should continue part two. So that was a good example of a story that after it was published lingered in my mind. I wish I had more experiences like that, because I really love the novella form. But usually, when I write a short story if it’s about 25 pages long, that’s the end. And I can’t make it any longer.

Phoebe: I think that answer will segue nicely into this question. The love canal has embedded itself into our nation’s consciousness as a symbol of the effects of corporate greed on people and the environment. This is not the first time you’ve written about the love canal. But in The Falls it’s given a much larger canvas. Is this a novel that has been germinating in your mind; that has expanded from “The Ballad of the Love Canal,” which you wrote much earlier?

JCO: I think I’ve always had it in my mind definitely I would write about Niagara Falls. I love that area. That area of New York State is very, very vivid in my mind, and kind of romantic and exciting. Of course what’s happened to the environment is just tragic. There’s just a lot happening there. The beauty of the falls, the natural wonder, which is so dazzling, and then what mankind or industrial mankind has done to that area: harnessing the Niagara River for electric power, and then building all these chemical factories up there. To me it’s such a natural area for drama, and human effort, and some people worked really very hard to turn that environment around and save the environment. And I wanted to honor those people in my novel and suggest how courageous they were back in the 1950s. The whole idea of environmental litigation didn’t exist. Now it’s pretty common. But those people are pioneers. They had a very, very hard time. So I wanted to honor those people; I see them as heroic. The natural area, the natural wonder of the falls, that’s very beautiful. I wanted to write about it for quite a while.

I also have a novella out called Rape: A Love Story that’s set in Niagara Falls. I wrote the two around the same time. I finished The Falls and I was still so caught up in Niagara Falls; I just wanted to stay with it. So I wrote this novella; it’s only about 120 pages. I wish I could do a little more with Niagara Falls. Maybe I will.

Phoebe: Why isn’t the novella a more popular form among writers and readers?

JCO: Well, let’s see. There may be some novellas out there that are packaged as novels. There are a lot of best-selling books that are packaged to look like novels that really are short, that could be 150 pages long. But the book can be made to look like 200 pages, in the printing. So I think it could still be a very popular form if it’s packaged in a certain way. But you’re right to suggest that if it’s packaged as a novella then it doesn’t seem to have quite the sales possibility, unless the author’s very, very famous.

Phoebe: In his fine biography of you, Invisible Writer, Greg Johnson asserts that your “Detroit novel”—them—served for you as a kind of microcosm of an America beset with racial problems, gaping class differences, and a capitalism gone amok. Niagara Falls seems to play a similar role in the new novel. Much of what occurs, from Dirk Burnaby’s stonewalling by corrupt political forces, to Ariah Burnaby’s stubborn determination to close her eyes to events around her, thus leading to the Burnaby family’s dissolution, seems emblematic of America today. When drafting the novel did you (think of) Niagara Falls as a microcosm of the United States today?

JCO: Oh yes. I definitely was, though I wasn’t necessarily thinking of them. I even thought that the name “love canal” is such a great title, even though it’s completely accidental and arbitrary. But just the idea of love canal; the words are very poetic. And it seems to suggest some sort of allegory, some symbolism. And then Niagara Falls: the idea of the falls meaning the “fall” like the fall from the Garden of Eden. I had always anticipated that.

Phoebe: In the novel the falls assumes a mythic-demonic character with the power to charm, to draw in, and to kill. Yet it is also curiously neutral. One thinks of Hawthorne’s old evil forest in “Young Goodman Brown”—a place filled with spirits that test Young Goodman Brown in his faith. Was it a conscious effort on your part to re-imbue Niagara Falls with a sense of its awe-inspiring mythology?

JCO: Yes, I was definitely thinking of that. I had looked into some of the myths and Indian lore surrounding the falls. I put a little bit of that in the novel. The Niagara Indians and some of their beliefs and rituals having to do with the Niagara River and the falls: their ideas of sacrifice, that sort of pre-Caucasian America. I wanted to suggest that. When you actually stand in front of the falls it’s completely primeval. You might as well be there in the year 1, because it’s not necessarily in the 21st century. It’s only when you step back and move away from the falls, back into the city, back into the country that you’re caught up in our present day history, which is so perilous and complicated.

Joyce Carol Oates is a recipient of the National Medal of Humanities, the National Book Critics Circle Ivan Sandrof Lifetime Achievement Award, the National Book Award, and the PEN/Malamud Award for Excellence in Short Fiction, and has been nominated for the Pulitzer Prize. She has written some of the most enduring fiction of our time, including We Were the Mulvaneys;Blonde, which was nominated for the National Book Award; and the New York Times bestseller The Accursed. She is the Roger S. Berlind Distinguished Professor of the Humanities at Princeton University and has been a member of the American Academy of Arts and Letters since 1978.

K.E. Semmel was the assistant fiction editor at Phoebe in 2004 and the fiction editor in 2005. He was especially happy to publish Joshua Ferris (luck) and Joyce Carol Oates (a favorite writer and fellow western New York native). He is now a writer and literary translator whose work has appeared in Ontario Review, The Washington Post, The Writer’s Chronicle, Redivider, Hayden’s Ferry Review, World Literature Today, Best European Fiction 2011, Publishing Perspectives, and elsewhere. His translations include, among others, Karin Fossum’s The Caller; Jussi Adler Olsen’s The Absent One; Simon Fruelund’s Civil Twilight and Milk and Other Stories; Erik Valeur’sThe Seventh Child; Naja Marie Aidt’s Rock, Paper, Scissors; and, in 2016, Jesper Bugge Kold’s Winter Men and Thomas Rydahl’s The Hermit. He is the recipient of numerous grants from the Danish Arts Foundation and an NEA 2016 Literary Translation Fellow. For nine years he has written countless drafts of what he hopes will be his first published novel. He edits the SFWP Quarterly and hosts “Translator’s Cut,” an interview series that travels the globe interviewing translators about their work. Find him online at kesemmel.com. Twitter: @kesemmel.