Sherry Chandler

Sherry Chandler

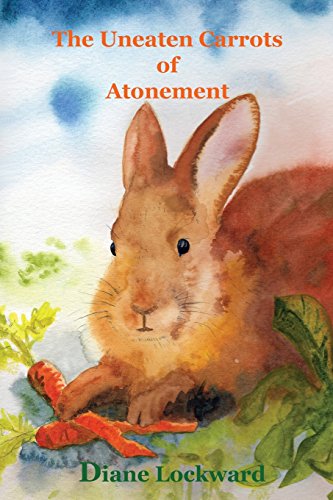

The Uneaten Carrots of Atonement.

by Diane Lockward

Wind Publications

ISBN 978-0-9969871-1-0

Those who come to Diane Lockward’s The Uneaten Carrots of Atonement expecting her usual lush color won’t be disappointed, though they may be surprised—three of the book’s five sections end with a poem addressed to a color. But bright as they begin, these poems move toward the darker side of the world we live in. In “Why Yellow Makes Me Sad,” the color of goldfinches and sunflowers ends as “the color of terror,” a reminder of the U.S. government’s color-coded threat advisories after the towers fell. “A Polemic for Pink,” that softest of colors, ends with Jackie Kennedy in Dallas,

her pink Chanel suit like a drift

of blossoms blown across her husband’s body.

“The Color of Magic” is the “red / satin dress sparking flames” to the “wail of the sax,” sexiest of instruments. That infernal “red satin dress in flames,” only one vowel away from Satan, returns in “Dreaming to Lionel Richie’s ‘Dancing on the Ceiling.’” This time it is accessorized with “red leather spikes setting the floor on fire.”

The book’s preface, “My Arty Ars Poetica, a Cento,” declares “Misery is universal. The only / math I know is balance. . . . / I make beautiful the moments of terror.” Are we to take this cento’s gathering of poetic voices as a guide not just to this book but to all of poetry? If so we must also consider that the word “arty” in the title blows off the apparent seriousness.

Such ironic undercutting begins with the title. Its juxtaposition of the spiritual with the trivial is reinforced by cover art featuring a somewhat blank-faced bunny, paws on a couple of deflated carrots. On evidence of the title and the cover art, a bookstore browser might expect whimsical content. She would soon be disabused. Along with those carrots, Lockward serves up a menu of broken marriages, lost or abused children, and the recurring appearance of a sinister father. For example, in the sestina “Why I Read True Crime Novels,” the speaker explains:

It’s always someone else’s family, not ours.

It’s down the street, across town, not in our house.

I’m merely brushing off my father’s hand.

I’m still intact, unbroken.

Is she?

Can a novel be true?

The portentously titled “Original Sin” opens the book proper. In it a bunny’s tail is torn off, a false confession is elicited, and a violent punishment meted out. The speaker’s father assumes she is guilty, therefore she concludes she must be “as guilty as those unbaptized babies / in Purgatory.” “Born bad,” because of original sin, how is the speaker to atone for allowing harm, for wishing to do harm, to a vulnerable creature in her care? Ultimately, the rabbit is found dead in its cage alongside those uneaten carrots. Atonement is not easily made.

Warned by the ars poetica to look for misery, terror, and balance, the reader opens Part Four to “Eminent Domain” and discovers the death of another bunny. As “original sin” is a religious concept, so “eminent domain,” the state’s right to seize private property for public use, is a secular one. These two tales of bunnicide balance like a see-saw, the priest on one end and the sheriff on the other. Here the state is represented by a “large and terrifying” dog that has killed a child’s pet rabbit. This time the woman swings the punishing strap. The dog, “a king come to claim this patch of earth,” is suddenly bloody and whimpering. Using the strap “as her father had done,” the speaker sends the dog running, buries her child’s pet inadequately “under a pile of leaves,” clears uneaten carrots from its cage, and sits on the porch awaiting her daughter, “a mother at last”—and empowered at last.

She would not speak

of revenge, how it had seized her, how good it had felt,

knowing she could split a boulder with her fist.

Though it deals with terror, this collection doesn’t stray far from suburban tidiness. The wild is violent and unwanted. Wild turkeys invade the yard early and late. In “How Heavy the Snow,” they “spread across the yard, / an army invading” and in “The Third Egg,” they “cast long, dark shadows.” The speaker fears these shadows will touch her belly “beating with child.” Aside from turkeys and dogs, the wild is represented by a dumpster rat, savoring a rare cube of cheese, and the cat who kills it just as it takes the first bite. Children are threatened by dogs, the bird feeder is threatened by squirrels and, in a dream vision, a line of ants is “like a single black hair from my lover’s groin.” In the penultimate poem, “Sign,” the bunny returns as “a soft rabbit [that] still lives inside you . . . and brings you back to the park,” another place where nature is tamed.

Lockward serves a banquet for the senses, but darkness lurks at its heart. We feel “The Pull of Bones,” the “compulsion of dirt and the dead,” consider eminent domain, atonement, original sin, and the semi-damned in Purgatory. Lockward serves a banquet for the senses, but darkness lurks at its heart, offering universal misery balanced through repetition and mirroring—offering the possibility that some terrors can be beautiful.

Sherry Chandler has published four collections of poetry, most recently The Woodcarver’s Wife which has been described as “quaint but smoldering”. She has a BA from Georgetown College and a traditional MA in English literature from the University of Kentucky. Her work has received the Betty Gabehart Award for poetry and three nominations for a Pushcart Prize. Her reviews have appeared in several periodicals, including Rain Taxi, Poet’s Quarterly, Rattle, and Still:The Journal. She has received financial support from the Kentucky Arts Council and the Kentucky Foundation for Women. Chandler lives on a small farm in Bourbon County with her husband, the woodcarver TR Williams.